Day 11

I didn’t set out to keep a Lenten blog about the Stations of the Cross. My plan was to write a 40 day devotional waaaaaaay in advance of the start of Lent. But, life got in the way of my plans and I decided that I would make blogging about the stations my Lenten practice. With every one of my projects, I’ve tried to create new ways for people to engage with the material. When I released Stations of the Cross: Mass Incarceration, I included a free PDF download of a study guide. I paired each station with an essay about the issue that the artwork addressed. It’s been interesting to re-visit these early projects.

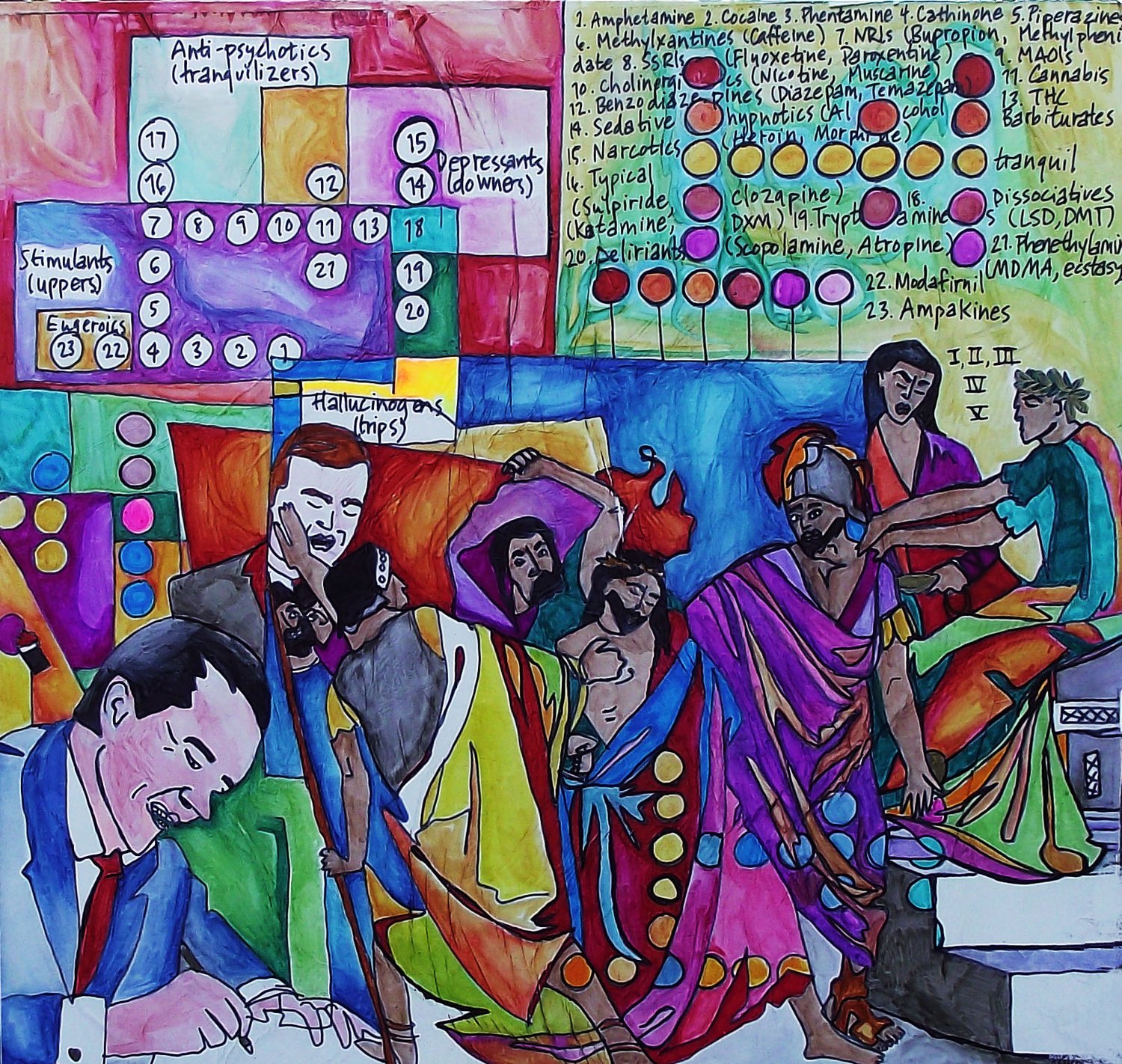

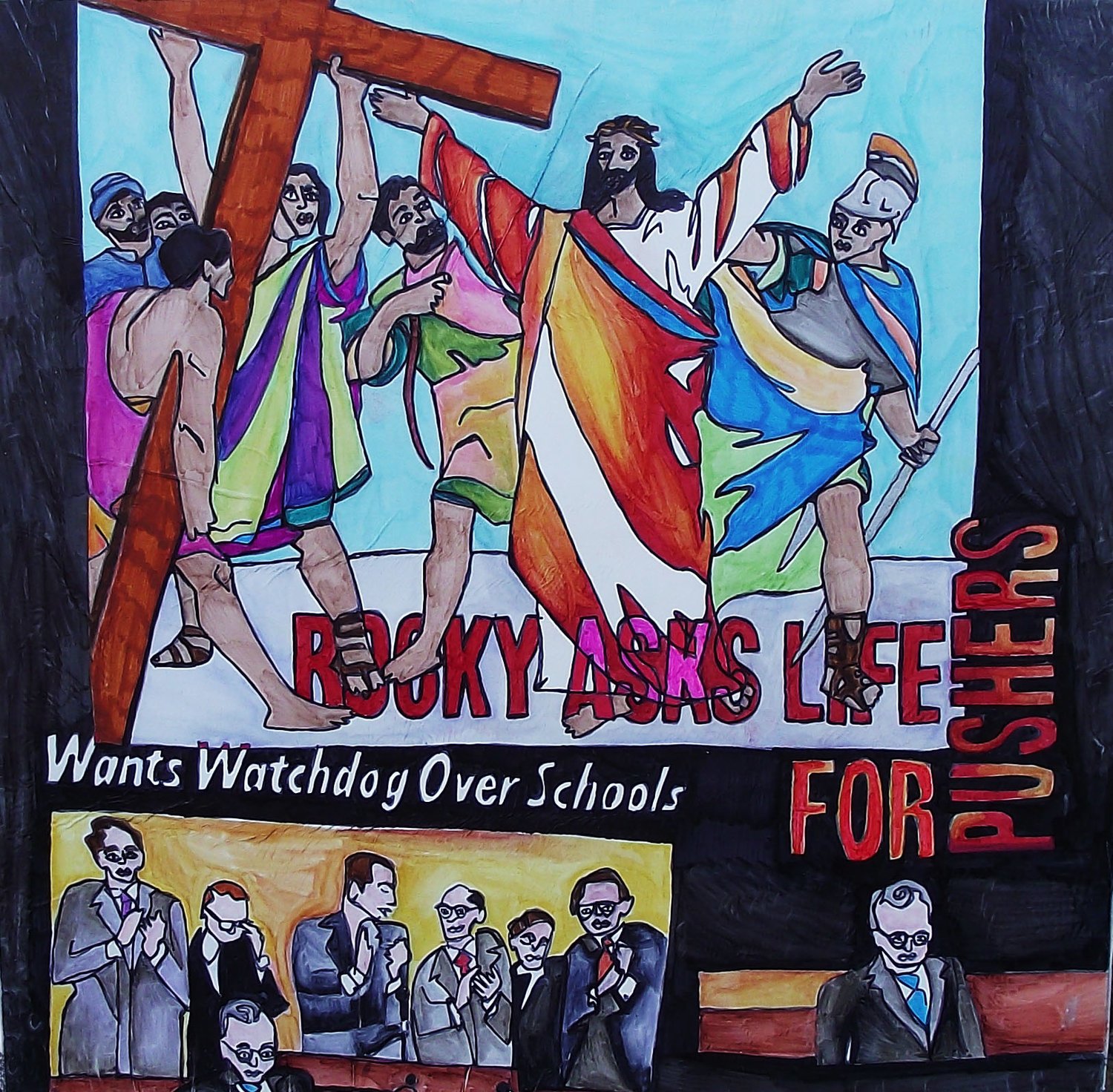

An overarching theme of this series is the War on Drugs. The short essay below is from the opening essay in the study guide - it went along with the first station. I have included in the post a side-by-side of the first two stations in this series - both feature moments from the history of the War on Drugs. Like the LGBTQ+ series that precedes it, this series incorporates historical events into its narrative. The essay below was my attempt at trying to provide a historical framework to the series.

From The Stations of the Cross: Mass Incarceration Study Guide, 2013

This series begins with the pairing of an image of Pontius Pilate washing his hands after ordering the crucifixion of Jesus with one of Richard Nixon signing the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. In 1970, Richard Nixon declared illegal drugs “public enemy number one” and out of this calculated attempt to appeal to law and order conservatives came the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (CDAPCA), a piece of legislation that put into motion the war on drugs as we now know it. As Michelle Alexander explains in The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, “the Act included a civil forfeiture provision authorizing the government to seize and forfeit drugs, drug manufacturing and storage equipment, and conveyances used to transport drugs.” This provision allowed for police departments to increase their budgets through the possession of property or cash seized based on the suspicion of illegal drug activity. The sudden influx of money into police budgets is directly responsible for the explosive proliferation of paramilitary units in narcotics departments in cities across the United States. While SWAT (Special Weapons and Tactics) teams were in use before the CDAPCA, they were used sparingly and in extraordinary circumstances. According to Alexander, in 1972 there were only a few hundred drug raids by SWAT teams. By the 1980s, there were thousands; in the 90s tens of thousands, and in 2001 more than 40,000.

The exponential increase in the deployment of SWAT teams is emblematic of the extent to which the war on drugs has destroyed Fourth Amendment protections against “unreasonable search and seizures.” Michelle Alexander concludes that: “The absence of significant constraints on the exercise of police discretion is a key feature of the drug war’s design. It has made the roundup of millions of Americans for nonviolent drug offenses relatively easy.”

Not all of the Stations address the War on Drugs directly, but the series begins with the signing of the CDAPCA because it marks the moment at which political rhetoric around drug use became a militarized force. In the years since the start of the War on Drugs, the penal population in the United States went from roughly 300,000 to over 2 million. Of the more than 3,200 inmates in American prisons serving life sentences without the possibility of parole, more than 80% of them are incarcerated for non-violent drug offenses. Of these inmates serving life sentences without parole, 65% are African American, 18% white, and 16% Latino.

It is our own individual vulnerabilities, traumas, and failings that create within us wells of compassion. I care passionately about the issue of mass incarceration because of the relationships that I have had with students through my experiences teaching art within the American prison system. What I have found is that there is deep truth in these words of the Talmud: “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.” Around every human life revolves an entire world of relationships, of loves and intimacies, of heartbreaks and trauma, and when a person is incarcerated a whole world is shattered. For this reason, the decision to send a person to prison must be reached justly and our current legal system is incapable of doing that. My hope is that by telling the story of Jesus’ crucifixion with images and stories from inside the realities of the prison system, viewers can come into a fuller understanding of both.